Building a New Life in America

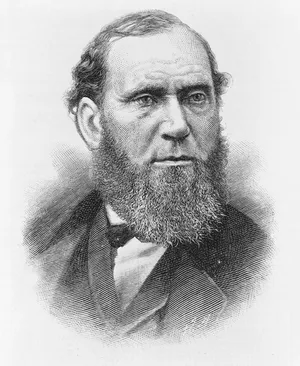

Born in 1819 in Glasgow’s working-class Gorbals district to a retired policeman, Allan Pinkerton left school at the age of ten after the death of his father to train as a cooper.

Figure 1. Allan Pinkerton, illustration from Harper's Weekly, vol. 28, July 1884.

In the late 1830s, he became active in the Scottish Chartist movement, a mass working-class campaign demanding democratic reforms like universal male suffrage, secret ballots, and equal electoral districts. Pinkerton even traveled to Chartist rallies and became something of a local Chartist leader. When Parliament met armed Chartists with deadly force, the movement faltered. By 1842, authorities in Scotland were suppressing Chartism and reports indicate a warrant was issued for Pinkerton’s arrest. Fearing persecution, Pinkerton fled Scotland in 1842 to America.

Early Days

Pinkerton arrived in New York in 1842. There, he heard of Dundee, a new Illinois settlement founded by Scottish immigrants Fox River northwest of Chicago. Upon arriving in Dundee, Pinkerton built a log cabin, established a cooperage business, and sent for his wife from Scotland. His small barrel-making shop thrived, and by the mid-1840s he employed several men and had earned a reputation as honest and industrious. Pinkerton was also an avid reader, and during this period he encountered Frederick Douglass’ antislavery writings. Deeply moved by abolitionism, Pinkerton embraced the anti-slavery cause. He joined Chicago’s abolitionist circles and even attended secret fundraising meetings in 1859 for John Brown’s raid. Moreover, Pinkerton’s Dundee farm became a stop on the Underground Railroad, sheltering fugitive slaves on their northward journey to freedom.

An Accidental Detective

In 1847, Pinkerton was collecting firewood on a remote island in the Fox River near Dundee when he stumbled upon a group of counterfeiters. He observed them for several days before alerting the local sheriff, leading to the arrest of the counterfeiters. Local merchants, whose businesses had been threatened by the rampant counterfeiting, hailed Pinkerton as a hero. So impressed were the community that they asked him to solve other crimes.

Soon, Pinkerton was serving as a deputy sheriff of Kane County and then, in 1849, as part-time deputy sheriff in neighboring Cook County. By early 1850, he had become Chicago’s first full-time police detective.

Founding the Pinkerton Agency

In the 1850s, American society was being rapidly reshaped by industrialization and urbanization. Cities like Chicago were booming, but its police forces were plagued by inefficiency and corruption. The Panic of 1857 also left urban police severely understaffed, and by 1860, despite having a population exceeding 100,000, Chicago employed only 67 police office officers. Recognizing the demand for a centralized approach to law enforcement, Pinkerton partnered with Chicago attorney Edward Rucker to found the North-Western Police Agency (later renamed Pinkerton & Company) in 1850, offering professional investigative and security services, particularly to railroads and businesses struggling with theft and fraud. The agency quickly gained prominence in the 1850s for solving several interstate train robbery cases, bringing Pinkerton into contact with Illinois Central engineers like George B. McClellan and the railroad’s lawyer Abraham Lincoln. Pinkerton’s success prompted him to resign from public office in 1855 and to devote himself full-time to his detective agency (by then called the Pinkerton National Detective Agency) headquartered in Chicago.

Breaking Barriers

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency quickly distinguished itself not only by its methods but also by its people. Allan Pinkerton was remarkably progressive in his hiring practices, employing women and minorities at a time when such practices were extremely uncommon. In 1856, he hired Kate Warne, a 22-year-old widow from New York, as the agency’s first female detective and the first professional female private detective in American history.

Figure 2. Portrait of Kate Warne, Chicago History Museum

Though skeptical at first, Warne convinced Pinkerton that women could gather intelligence in ways men could not: by befriending the wives and girlfriends of suspects.

Warne soon proved her value in an 1858 investigation of a high-profile Adams Express Company embezzlement case. Posing as a friend of the suspect’s wife, Warne gained the woman’s trust and learned the location of nearly $10,000 in stolen bonds. Impressed by her success, Pinkerton established a dedicated Women’s Bureau under her leadership.

Pinkerton also recruited immigrants like himself and even members of racial minorities. For example, during the Civil War, he enlisted an educated African American scout named John Scobell. Scobell, a former slave, gathered sensitive information by posing as a valet or servant, listening in on conversations, and then relaying that information back to Pinkerton.

Pinkerton knew that a well-dressed black man would draw little suspicion in the South, using the Confederacy’s racial prejudices to his advantage.

Foiling the Baltimore Plot

The agency’s first major national acclaim came on the eve of the Civil War. In early 1861, it uncovered a plot to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration. Rumors had reached Dorothea Dix that secessionists in Baltimore, Maryland, a slaveholding city on Lincoln’s planned route, intended to murder Lincoln as he changed trains there. Dix passed this news on to Samuel Morse Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad, who hired Pinkerton agents to investigate. Pinkerton operatives, including Kate Warne, infiltrated meetings of the pro-Confederate secret society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. The detectives gathered evidence that there really was a conspiracy to ambush Lincoln. Allan Pinkerton raced back to Philadelphia to warn Lincoln of the threat, persuading him to secretly slip through Baltimore during the night. Lincoln arrived in Washington, D.C., without incident, a success that made national headlines.

Civil War Service

When the Civil War began a few weeks later, Lincoln appointed Allan Pinkerton as chief intelligence officer for Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Operating under the alias Major E.J. Allen, Pinkerton and his network of operatives conducted some of the earliest examples of organized military espionage in American history. Disguised as surveyors, shopkeepers, or even Confederate soldiers, Pinkerton’s men infiltrated the South to learn enemy positions, fortifications, and plans. He also interviewed runaway slaves, Confederate deserters, and Southern refugees to map and estimate troop movements and strength.

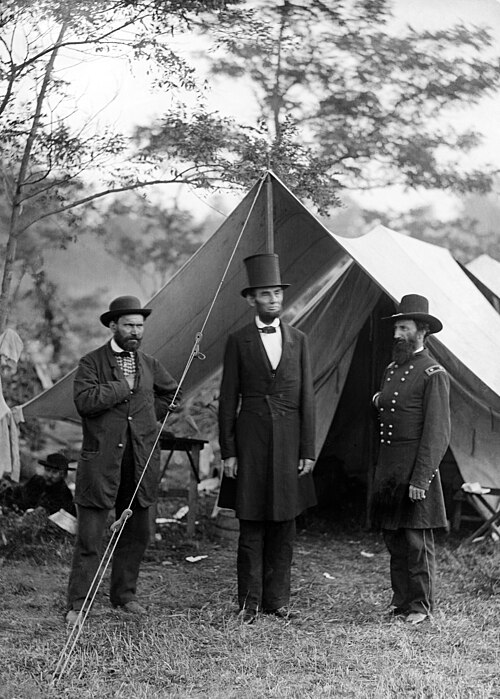

Figure 3. Photo of Allan Pinkerton, President Abraham Lincoln, and Major General John

A. McClernafter after the Battle of Antietam on October 3, 1862, Library of Congress

However, Pinkerton’s tenure as chief intelligence officer was controversial. In the summer of 1862, during McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, Pinkerton reported to McClellan that Confederate forces numbered well over one hundred thousand men, far above the true figure of roughly fifty to sixty thousand under General Robert E. Lee. This overestimate led the overly cautious McClellan to delay attacking, believing he was badly outnumbered, slowing the Union advance at Richmond. Lincoln eventually removed McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862, believing that his hesitancy was hindering the war effort, and Pinkerton went with him.

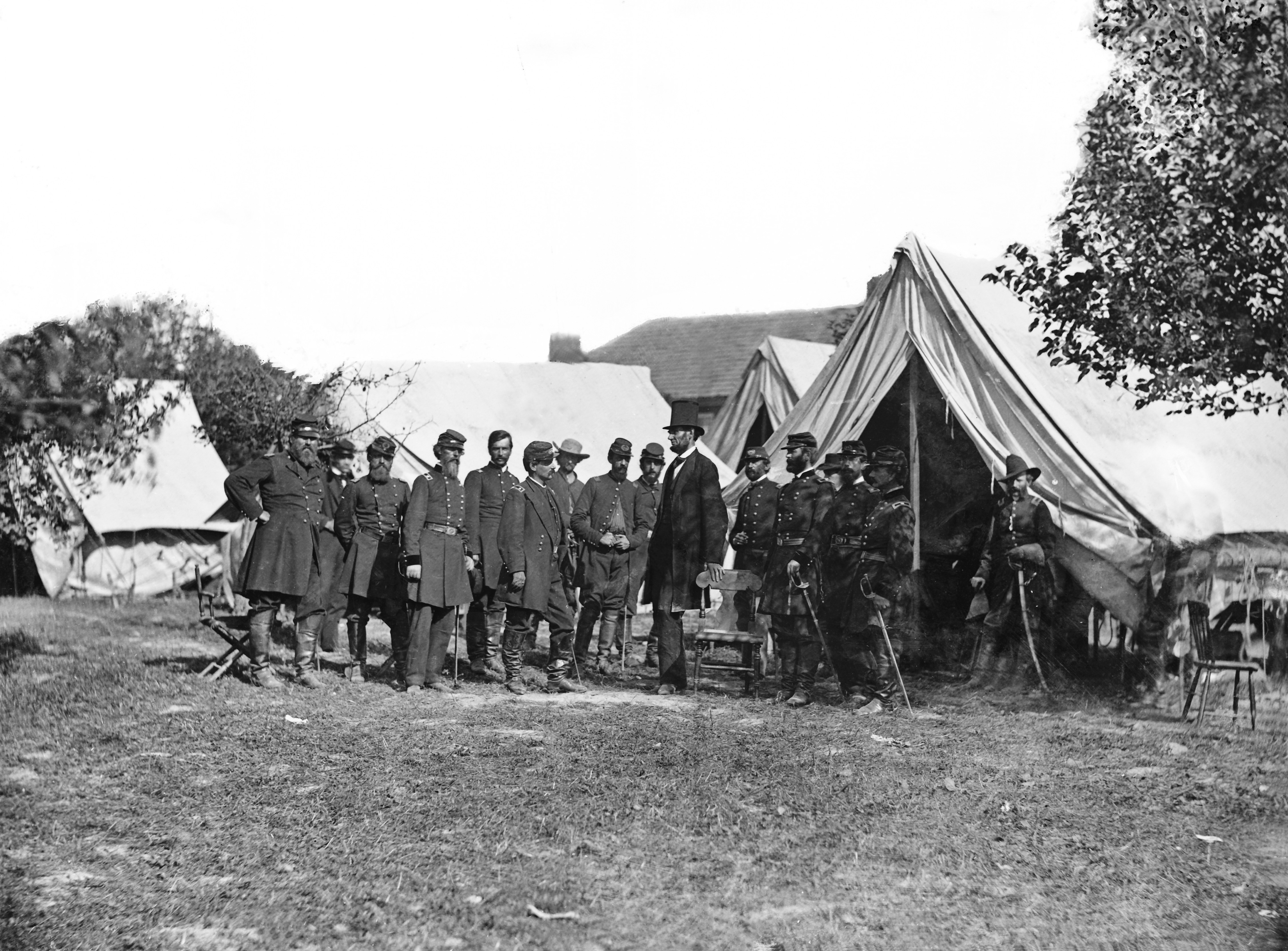

Figure 4. Photo of President Abraham Lincoln with Major General George B. McClellan and a group of officers during the Battle of Antietam on October 3, 1862, Library of Congress