Labor in the Gilded Age

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the United States experienced a period of rapid industrialization. The Gilded Age, spanning from the 1870s to the early 1900s, was a time of unprecedented economic growth in the United States, driven by advancements in industries like railroads, steel, and mining, transforming the nation into a global industrial leader. However, beneath this prosperity lay significant social and economic disparities. As immigrants and rural populations moved to cities in search of work, they often found themselves facing overcrowded housing, long hours in dangerous conditions, and low wages, all while robber barons reaped most of the rewards. These harsh conditions fueled the rise of organized labor movements such as the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which organized workers to demand better wages, shorter hours, and safer conditions.

From Detectives to Strikebreakers

In the 1870s, the Pinkertons began to shift their focus from traditional detective work to anti-labor espionage and strikebreaking, fundamentally altering the agency’s reputation. Economically, the concentration of industrial wealth in the hands of a few robber barons provided both the means and incentive to hire private armies to protect their profits and control their workforce. Socially, the rise of industrial capitalism saw mounting class conflicts between capital and labor. Between 1866, and 1892, the Pinkertons participated in 70 labor disputes and opposed over 125,000 strikers, signifying a departure from their earlier role as detectives and bodyguards. They infiltrated labor unions, gathered intelligence on organizers, disrupted strike activities, supplied armed guards to protect scabs, maintained blacklists of union activists, and recruited “goon squads” to intimidate workers.

Breaking the Molly Maguires

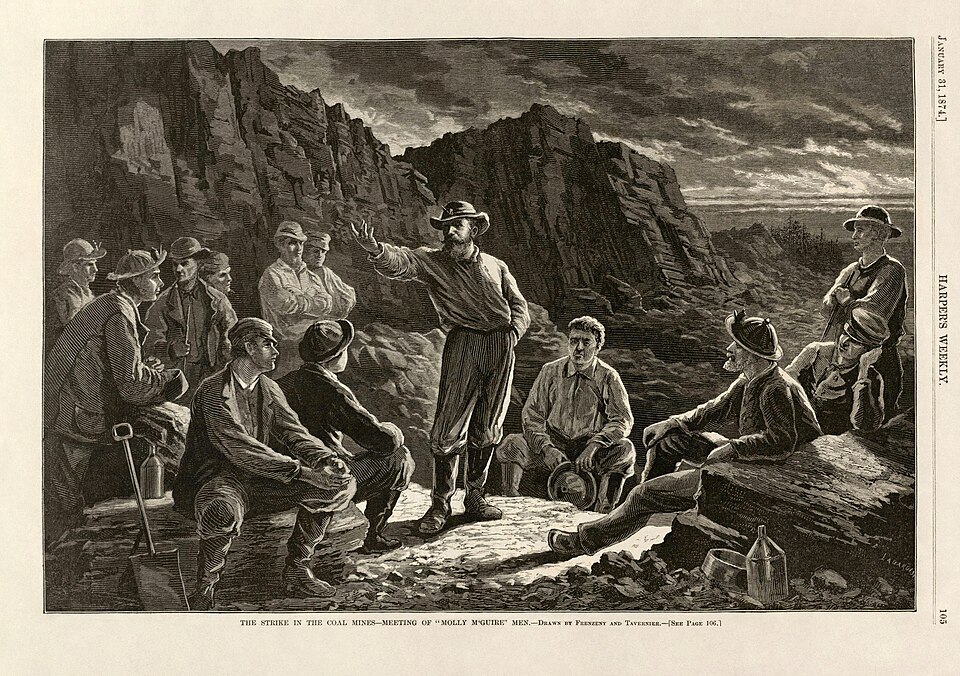

In the anthracite coal fields of Pennsylvania, Irish American miners faced discrimination and harsh working conditions, leading to the formation of a secret society known as the Molly Maguires. Allegedly responsible for acts of violence, including assassinations and sabotage, the group aimed to resist oppressive mine owners.

Figure 5. Molly Maguires meeting to discuss strikes in the Pennsylvania coal mines, Harper's Weekly, 1874

In 1873, Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, hired the Pinkertons to dismantle the organization. Pinkerton agent James McParland, under the alias James McKenna, infiltrated the group for over two years, gathering evidence that led to the arrest, conviction, and hanging of numerous members, ultimately leading to the downfall of the organization.

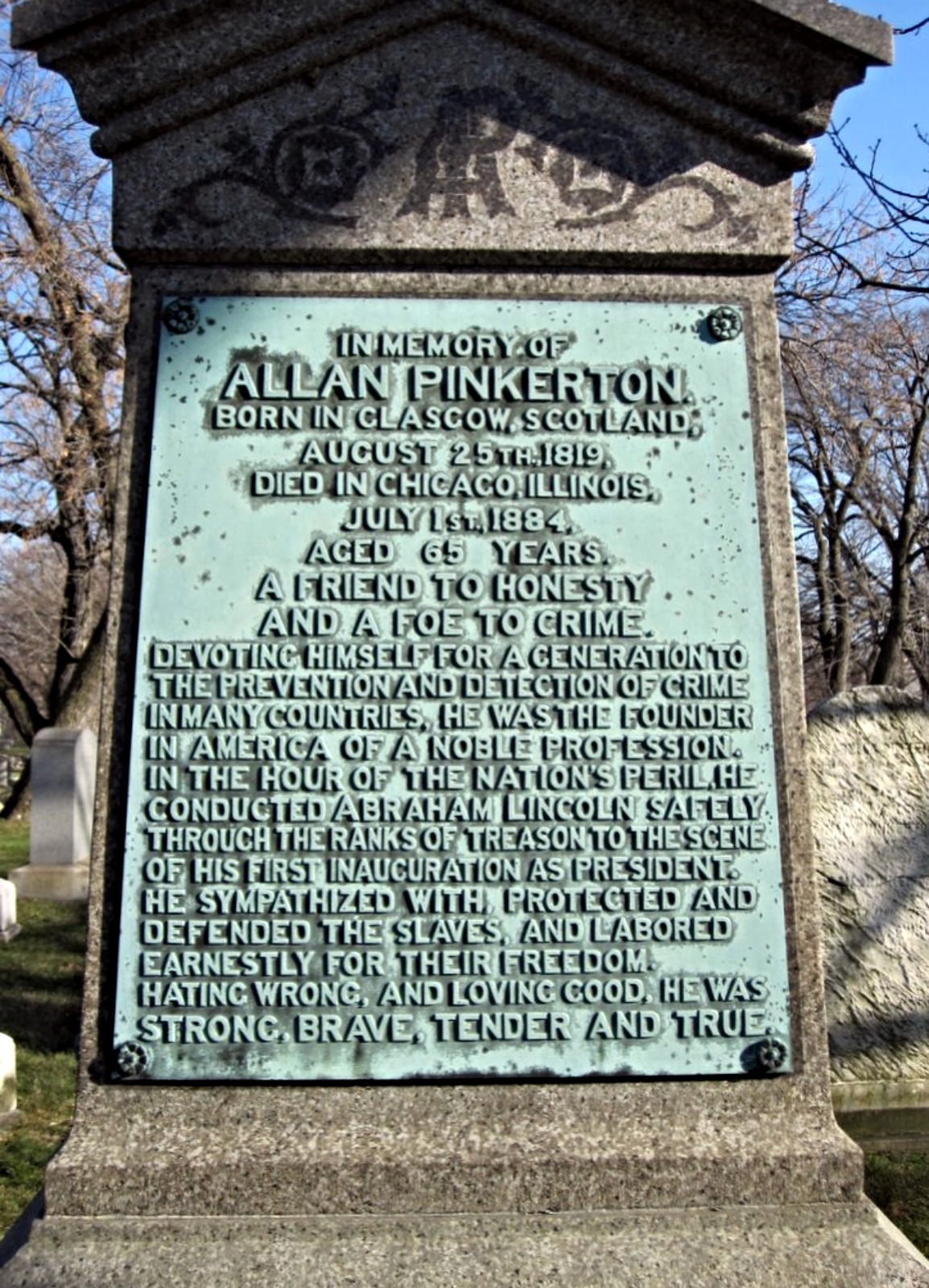

Death By Poodle

On July 1, 1884, Allan Pinkerton died from gangrene of the tongue. After his death, his sons took over the agency, which continued to grow and break strikes. By the 1890s, it had 2,000 detectives and 30,000 reserves, more men than the standing army of the United States.

Figure 6. Grave Site of Allan Pinkerton, Stephen Hogan

The Homestead Strike

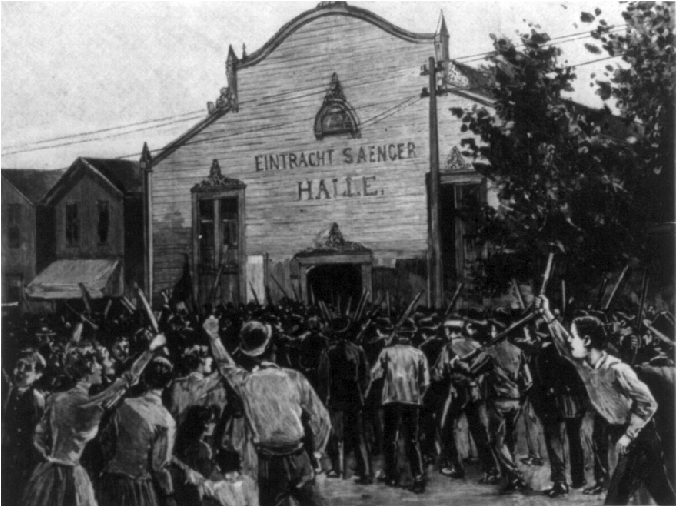

The 1892 Homestead Strike marked the definitive turning point in public perception of the Pinkertons, transforming them from respected law enforcement professionals into symbols of corporate oppression and violence. Henry Clay Frick, the chairman of Carnegie Steel, sought to break the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) by imposing wage cuts. When negotiations failed, Frick locked out 3,800 workers on June 29, 1892, and constructed a fortified fence around the plant.

On July 5, Frick hired 300 Pinkerton agents from New York and Chicago to secure the plant and protect strikebreakers. Arriving by barges on the Monongahela River at 4 a.m. on July 6, the agents were met by armed strikers and townspeople. A day-long battle ensued, resulting in three Pinkerton deaths, seven worker deaths, and numerous injuries. By 5 p.m. when the Pinkertons finally surrendered, they were brutally beaten by the crowd, including men, women, and children, as they were marched through town.

Figure 7. Illustration of Homstead mob assailing Pinkerton men, Harper's Weekly

The Pennsylvania governor deployed 8,500 National Guard troops to restore order and the strike collapsed by November, devastating the AA, whose membership plummeted from 24,000 in 1891 to 8,000 by 1895. The violence at Homestead was unprecedented in its scale and brutality. The sight of private agents engaging in deadly combat with American workers shocked the public and the press and turned public opinion against both the Pinkertons and Carnegie Steel. The battle was covered internationally and the song “Father was killed by the Pinkerton men” became popular nationwide, cementing the agency’s image as corporate mercenaries and enemies of the working class.

Men struck against reduction of their pay

Their millionaire employer with philanthropic show

Had closed the works till starved they would obey.

They fought for home and right to live where they had toiled so long

But ere the sun had set some were laid low;

There're hearts now sadly grieving by that sad and bitter wrong

God help them for it was a cruel blow.

God help them tonight in their hour of affliction

Praying for him whom they'll ne'er see again

Hear the poor orphans tell their sad story

"Father was killed by the Pinkerton men."

Ye prating poiiticians, who boast protection creed,

Go to Homestead and stop the orphans' cry.

Protection for the rich man ye pander to his greed,

His workmen they are cattle and may die.

The freedom of the city in Scotland far away

Is presented to the millionaire suave,

But here in Free America with protection in full sway

His workmen get the freedom of the grave.

God help them tonight in their hour of affliction

Praying for him whom they'll ne'er see again

Hear the poor orphans tell their sad story

"Father was killed by the Pinkerton men."

The Pullman Strike and the Birth of Labor Day

The Pullman Strike of 1894 began when workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company, led by Eugene V. Debs and the American Railway Union (ARU), protested wage cuts and high rents in the company town. As the strike expanded, workers began to disrupt railroad traffic nationwide. At its height, 250,000 workers participated in the strike and boycott, halting all rail service west of Detroit. In response, railroad companies hired private security forces, including the Pinkertons, to break the strike, protect railroad property, and intimidate strikers, often through violence. Ultimately, the National Guard was called in and up to seventy men were killed. In the wake of the labor unrest and in an attempt to appease American workers, Congress passed an act making Labor Day a legal holiday, which President Grover Cleveland subsequently signed into law.