Introduction

The remainder of 1846 was spent traveling across 300 miles of Iowa to the Missouri River near present-day Omaha, Nebraska (“The 1846 Trek”; "Westward Migration"). During the winter of 1846-1847, the church established a temporary settlement known as Winter Quarters, where Brigham Young and his advisors carefully planned their westward migration (Birzer). Their goal was to settle in the Great Basin—then a loosely-governed region of Mexican territory beyond U.S. jurisdiction—where they hoped to find refuge from persecution and government interference (“Mexican-American War”). With the help of Thomas L. Kane, a sympathetic non-Mormon with ties to the Polk administration, the Saints secured permission to winter on Native American lands (Wickman). Young personally oversaw the preparations, which included gathering essential supplies such as portable boats, scientific instruments, and seeds. The leaders also sought advice from frontiersmen and Jesuit missionaries familiar with the Great Basin’s geography (“The Trail Experience”). To minimize conflicts and avoid competition with non-Mormon settlers traveling along the Oregon Trail, Mormon leaders chose a path along the north bank of the Platte River, as opposed to the south bank (“The 1847 Trek”).

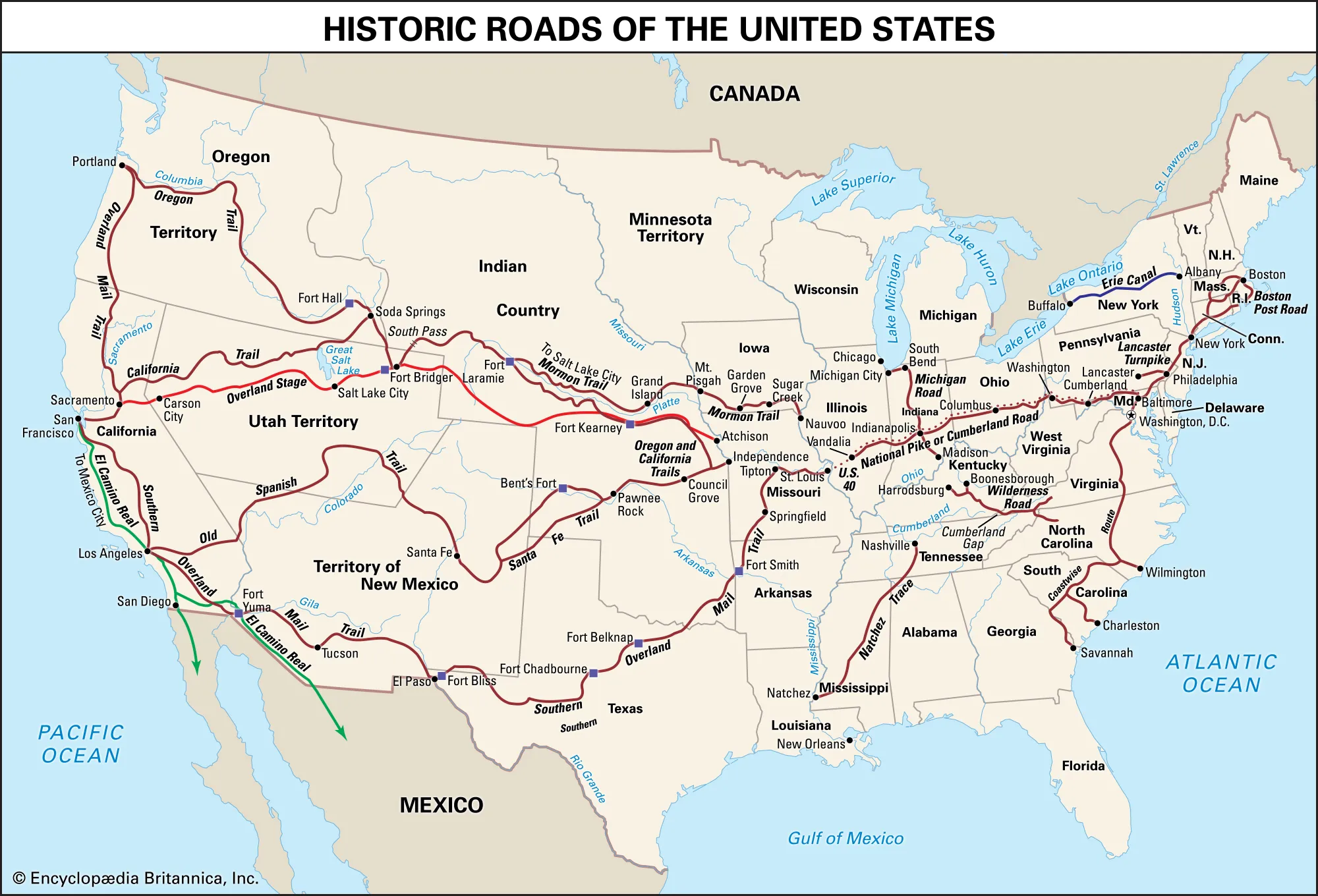

Figure 9. Map showing the Mormon Trail alongside other historic trails and roads across the United States

Arriving in Salt Lake Valley

Brigham Young’s vanguard company—comprising 143 men, 3 women, and 2 children—departed from Winter Quarters on April 5, 1847 (“The 1847 Trek”; “Mormon Trails”). The first scouts reached the Salt Lake Valley on July 21, 1847, with the main group arriving three days later, on July 24—a date now celebrated in Utah as Pioneer Day ("Westward Migration"). Upon arriving, Brigham Young, ill and confined to a wagon, sat up, gazed out at the valley, and, recognizing a conical peak that he had seen in a vision, declared, "This is the place, drive on." ("Brigham Young Arrived in Salt Lake Valley").

During their first week in the valley, the pioneers plowed and planted 53 acres with potatoes, peas, beans, corn, oats, and buckwheat, while explorers mapped the Great Salt Lake Valley and nearby canyons. About a month later, Brigham Young, along with 179 others, embarked on the 1,000-mile journey back to Winter Quarters to help more Saints cross the plains, arriving there just before Winter. Meanwhile, the 180 pioneers who remained focused on tending the crops and building a fort at what is now Pioneer Park in Salt Lake City ("Brigham Young Arrived in Salt Lake Valley"; Westward Migration)

Expanding Influence

The spring of 1848 brought new settlers to Utah, but not without hardship. That year, swarms of crickets ravaged the pioneers' crops. After much prayers and fasting, flocks of seagulls appeared and devoured the crickets, saving the harvest. This event, known as the "Miracle of the Gulls," is commemorated with a monument on Temple Square, and the seagull was later chosen to be Utah’s state bird. Despite these challenges, the Saints continued to grow and thrive. They established new towns, built schools, and established a government. Missionary work also expanded, particularly in Europe, where the church saw significant growth—especially in England, where over 17,000 people joined. The Book of Mormon was translated into several major European languages, as well as Hawaiian, further spreading the church’s influence (“Westward Migration”; "Crickets and Seagulls"). Despite the challenges, the Saints built communities throughout Utah and neighboring states, including Arizona, Nevada, Wyoming, Colorado, and Idaho. Between 1847 and 1900, they established around 500 settlements (Rood and Thatcher, "Mormon Settlement"; "Westward Migration").

The Mexican Cession

Following the end of the Mexican-American War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in 1848, ceding a vast amount of territory to the United States, including the region where the Mormons had chosen to settle. As a result, the Mormons once again found themselves under U.S. government jurisdiction ("Mexican-American War").

Push for Statehood

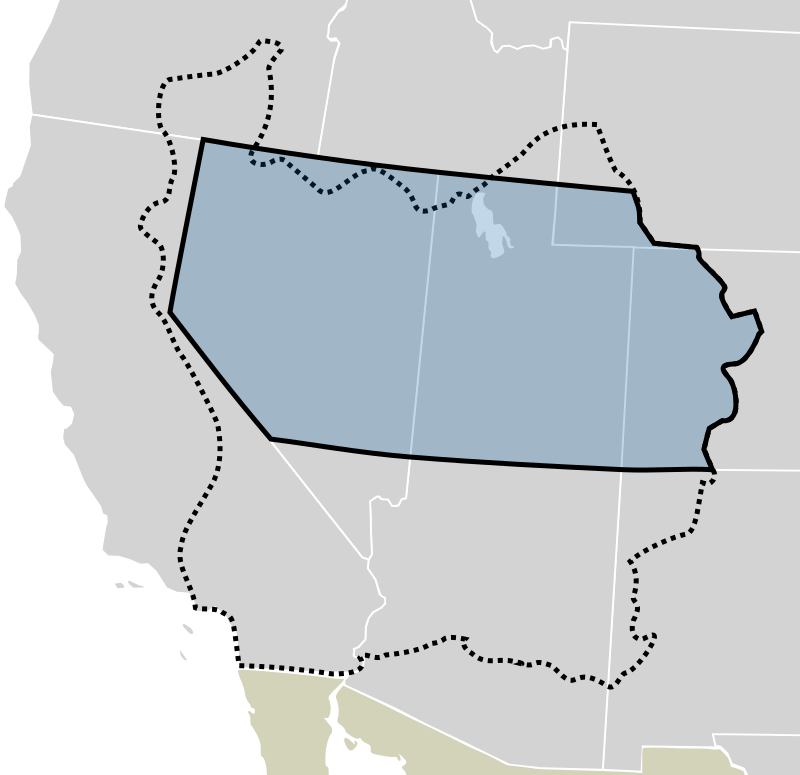

The Mormons' first attempt at attaining statehood was the proposal of the State of Deseret, a vast region encompassing the entire Great Basin and stretching east to the Continental Divide (see fig.10). The proposed boundaries included not only present-day Utah but also most of Nevada and Arizona, parts of southern California (including the port of San Diego), Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Oregon, and Idaho. By March 10, 1849, the constitution for Deseret was finalized, and two days later, officials were elected, with Brigham Young as governor. However, Congress rejected Deseret’s application, primarily due to their lack of the 60,000 eligible voters required for statehood and the proposed state's massive size. Instead, on September 7, 1850, the Senate passed a bill establishing the much smaller Utah Territory, rejecting the name Deseret and decreasing its massive land area (Thatcher).

Figure 10. Map of the proposed State of Deseret (dotted line) and Utah Territory (blue, black outline) overlaid on the modern U.S. map. Boundaries are approximate. derivative work: Mangoman88 (talk)Blank_US_Map.svg: User:TheshibbolethWpdms deseret utah territory legend.png: User:Tsujigiri, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The House approved the bill on September 9, and President Millard Fillmore signed it into law the same day. On September 20, President Fillmore announced his own list of territorial appointments, most of whom were non-Mormons, which the Senate confirmed on September 30. While most of the originally elected officials were replaced, Brigham Young was retained as governor (Thatcher).