Introduction

Following persecution in Missouri, members of the church sought refuge in Quincy, Illinois in January of 1839. The compassionate residents supported the Mormons until they could get back on their feet and establish a new settlement. On April 16, a sympathetic guard helped Joseph Smith and other imprisoned Mormons escape. When Joseph Smith and other church leaders arrived in Illinois, they selected a site in Hancock County called Commerce for their new settlement. They renamed it Nauvoo, a Hebrew word that translates to “to be beautiful.” Nauvoo started out as a disease-ridden swamp, but the Saints quickly drained the nearly 800-acres of land and transformed it into a thriving community. In 1840, the city’s charter was also approved. This charter not only granted the Mormons legal protection against mob attacks but also allowed Nauvoo to establish its own court system, university, and militia, known as the Nauvoo Legion. It also stipulated that no resident of Nauvoo could be arrested without a writ of habeas corpus issued by a city judge to prevent Mormons from being illegally seized by mobs or sheriffs, as had happened in the past (“Nauvoo”; “Nauvoo Mormon Period”). In 1842, Smith assumed the role of mayor after the previous mayor was expelled from Nauvoo and excommunicated from the church for adultery (Hedges and Smith). By 1844, Nauvoo's population had grown to nearly 12,000, rivaling that of even Chicago (Boyd and Black).

Growing Tensions

In 1843, Smith received a revelation from God instructing him to practice polygamy, or plural marriage. He later shared this practice with his most trusted associates. Initially kept secret, polygamy would eventually contribute to both internal and external tensions. As the Mormon population grew, non-Mormon residents of Hancock County became increasingly wary of the Mormons’ political influence and Joseph Smith’s power. Not only was Joseph Smith serving as the church president, he was also the mayor of Nauvoo and the lieutenant general of the Nauvoo Legion ("Nauvoo"). Early 1844 was also a difficult time for the church, with dissent spreading rapidly throughout the church. Some members opposed polygamy and others questioned Smith's prophetic authority (“Nauvoo”). To address the growing criticism towards himself and the church, Smith declared his candidacy for the presidency of the United States. Though he probably didn't expect to win, he wanted to share Mormon views with a broader audience (“Joseph Smith’s Campaign”).

The Assassination of Joseph Smith

On July 7, 1844, former Mormon leader William Law, disillusioned with the church, published the Nauvoo Expositor, a controversial paper accusing Joseph Smith and other leaders of various wrongdoings (Foster).

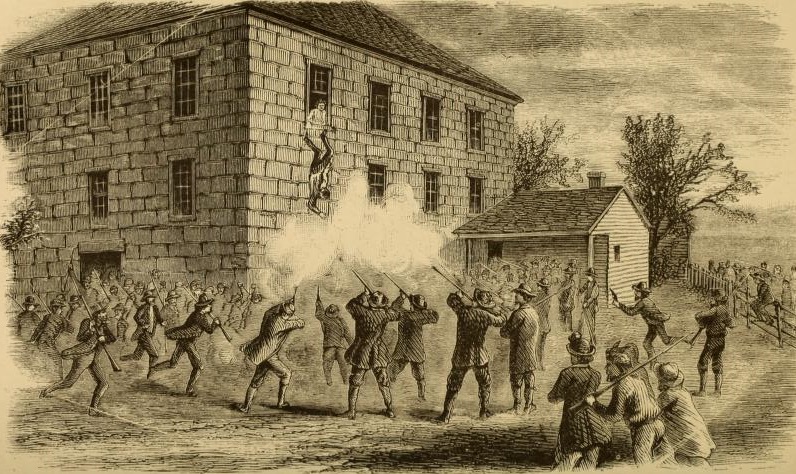

Joseph Smith and the Nauvoo City Council ordered the destruction of the press and its publications, a decision that caused a riot and for many to call for Smith’s arrest. Charged with inciting a riot, Joseph Smith surrendered on June 22, 1844, after Governor Thomas Ford promised protection and a fair trial. Despite the governor's assurances, the situation in the county jail in Carthage, Illinois, began to deteriorate rapidly. On June 27 at around 5:00 p.m., a mob, including members of the local militia that was assigned to protect Smith, stormed the jail, overpowering Joseph and his brother, Hyrum, who were trying to hold the door. In the ensuing chaos, Hyrum Smith was shot and killed instantly. Joseph fired his gun in self-defense, wounding three attackers before his weapon jammed. He then moved towards the window where he was shot several times and fell to the ground below (see fig.7) (“Nauvoo”).

Figure 7. Depiction of the Death of Joseph Smith from The Rocky Mountain Saints by Thomas Brown Holmes Stenhouse, 1873.

Departure From Nauvoo

The martyrdom of Joseph Smith, along with his brother Hyrum, sent shockwaves through the Mormon community. Many of the church's opponents believed that Mormonism would collapse without Joseph. However, the opposite proved true. Within a year of Joseph's death, nearly 4,000 new converts joined the church. In August 1844, a conference was convened to determine the church's new leadership. The assembly ultimately voted to accept Brigham Young as their leader. Yet, opposition to the Mormons persisted. In January 1845, the Illinois legislature overwhelmingly revoked Nauvoo’s city charter, effectively disbanding its civil government and escalating tensions. Later that year, the mob leaders responsible for the murders of Joseph and Hyrum were acquitted in a sham trial that excluded Mormon witnesses. By the fall of 1845, it became clear to Mormon leaders that remaining in Nauvoo was no longer safe. Brigham Young and other church leaders began preparing for a westward migration to the Rocky Mountains as prophesized by Joseph Smith many years prior. In February 1846, the first group of Mormon pioneers crossed the frozen Mississippi River into Iowa, marking the beginning of the Mormon Exodus ("Nauvoo").

The Battle of Nauvoo

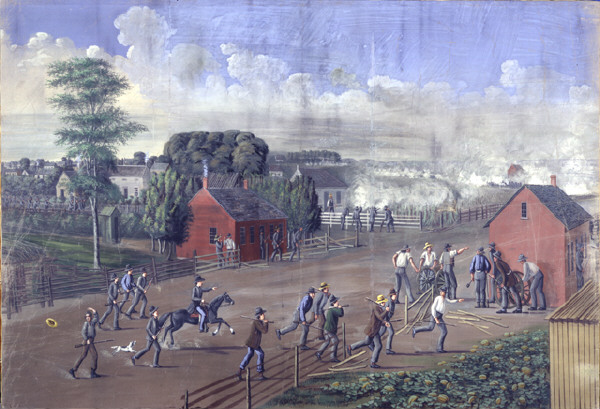

Seeing as most Latter-day Saints had already left Nauvoo earlier that year to begin their westward migration, the city was largely abandoned by the summer of 1846. Only a few hundred remained—largely impoverished or ill members of the Church who were unable to join the exodus. Though they intended to stay peacefully, tensions with nearby communities escalated. Frustration among church opponents grew, and by July, threats of violence, kidnappings, and physical assaults became common. Despite attempts by the state militia to maintain order, their efforts were largely ineffective. A treaty was negotiated to prevent bloodshed, but it failed to appease the mob, which demanded the immediate expulsion of the remaining Saints. On September 10, 1846, a mob of roughly 1,000 men advanced on Nauvoo (see fig.8). The city's defenders, numbering fewer than 150, were vastly outmatched and poorly equipped, relying on makeshift weapons like a cannon fashioned from a steamboat shaft. Employing guerrilla tactics, they built barricades, launched hit-and-run attacks, and conserved their limited ammunition to hold off the mob for a week. However, on September 16, 1846, realizing further resistance was futile, the Saints negotiated a surrender. The agreement required them to leave Nauvoo and cross the Mississippi River, though it did little to quell the mob’s hostility. The next day, mobs entered the city, looting homes, searching wagons, and confiscating weapons. Some Saints were forcibly driven out at gunpoint, many left destitute and ill-prepared for the journey ahead. The exiles camped along the western banks of the Mississippi for several days, awaiting rescue efforts to bring aid and supplies (Lee).

Figure 8. Depiction of The Battle of Nauvoo by Carl Christian Anton Christensen, 19th century.