Establishment of Caldwell County and Far West

In 1836, after several unsuccessful attempts to reclaim their land in Jackson County following their expulsion, the Mormons agreed to a legislative compromise led by Alexander William Doniphan of the Missouri legislature. This compromise involved establishing Caldwell County as a designated area for Mormon settlement by dividing Ray County into Ray, Caldwell, and Daviess Counties (see fig.2) (Jones). Although there was no formal legal agreement designating Caldwell County specifically for Mormon settlement, there was a general understanding that Mormons would be restricted to settling in only that area to help maintain peace and provide the Mormons with the level of autonomy that they desired (Hamer).

Figure 2. Latter-day Saints Places of Interest, Missouri by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

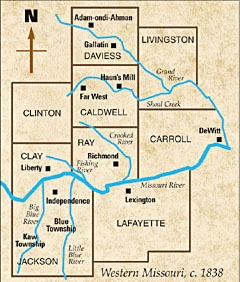

Bunkham's Strip, a twenty-four-mile-long and six-mile-wide stretch of no-man's land lying just south of Caldwell County, acted as a barrier between the Mormons in Caldwell County and the non-Mormons in Ray County ("Battle of Crooked River"). In 1836, the Mormons began establishing the town of Far West in Caldwell County as their headquarters within Missouri. However, after the church's original headquarters in Kirtland, Ohio collapsed amidst a financial crisis and internal dissent in 1837, the church relocated its headquarters to Far West, Missouri, attracting an influx of settlers (Birzer). Consequently, Mormons began establishing new colonies outside Caldwell County, such as Adam-ondi-Ahman in Daviess County and De Witt in Carroll County (see fig.3), arguing that the agreement only restricted major settlements in Clay and Ray Counties. Despite this, many non-Mormons perceived the expansion as a breach of the compromise, reigniting tensions as local settlers viewed the growing Mormon presence as a political and economic threat (Hamer).

Figure 3. A map of the nine counties in central western Missouri where Church history events took place by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Escalation of Conflict

A group of vigilantes from Clinton, Platte, and other nearby counties began to harass Mormons in Daviess County, forcing them to seek refuge in Adam-ondi-Ahman. In response, Mormon leaders mobilized militia forces and the Danites, a Mormon vigilante group. These groups retaliated by attacking and burning various Missourian settlements such as Gallatin, Millport, and Grindstone Fork. During these attacks, the Mormons looted property, destroyed homes, and displaced non-Mormon families (Knip).

The Battle of Crooked River and Missouri Executive Order 44

Fearing similar attacks, many non-Mormon families from Ray County fled across the Missouri River for safety. To maintain peace, a militia led by Samuel Bogart was assigned to patrol Bunkham's Strip. However, instead of remaining in the strip, Bogart crossed into Caldwell County, where he began harassing, disarming, and threatening the Mormons. When news reached the Mormon leaders that some of their people had been taken prisoner and were at risk of execution, they quickly organized an armed rescue party. The ensuing battle became known as the Battle of Crooked River, named after the river by which it was fought. The Mormons clashed with Bogart's militia, successfully driving them back but suffering significant casualties themselves. Exaggerated rumors that Bogart's entire company had been massacred spread panic across Missouri. Governor Lilburn Boggs, already unfriendly toward the Mormons, viewed the incident as an insurrection. On October 27, 1838, he issued Missouri Executive Order 44, also known as the "Mormon Extermination Order," declaring the Mormons enemies of the state and ordering their extermination or removal (Knip).

Figure 4. Map of northwestern Missouri, showing points of conflict in the Mormon Missouri War by John Hamer - English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link.

Hawn's Hill Massacre

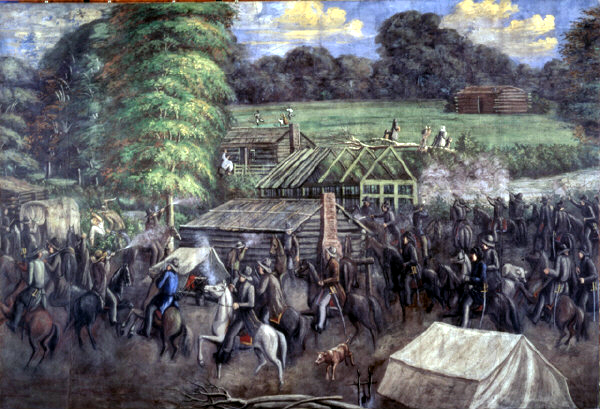

On October 30, 1838, a mob from Livingston County, Missouri attacked a Mormon settlement at Hawn's Mill. While women and most children hid in the woods, a group of Latter-day Saint men and boys took refuge in the blacksmith's shop. The attackers surrounded the shop, firing through the gaps in its roughly hewn log walls, killing those inside and even those attempting to surrender (see fig.5). After the initial assault, they dragged several young boys who had hidden under the blacksmith's bellows and executed them. The massacre resulted in the deaths of 17 Latter-day Saints and left another 12 to 15 wounded ("Hawn's Mill Massacre"). No Missourians were ever prosecuted for the violence ("What Happened at Hawn's Mill").

Figure 5. Depiction of the Hawn's Mill Massacre in Caldwell County, Missouri by Carl Christian Anton Christensen, 19th century.

The Fall of Far West

On October 31, Major General Samuel D. Lucas led a militia to besiege the Mormon stronghold at Far West. Mormon leaders, including Joseph Smith, surrendered and were ordered to be executed the following day ("Mormon-Missouri War of 1838"). However, Doniphan refused to carry out the order, saying that the court martial convened to try Joseph Smith and his followers was illegal under the law ("Alexander W. Doniphan").

Instead, Joseph and several others were imprisoned in Liberty Jail and scheduled to stand trial on charges of treason and murder. The Mormons were disarmed, forced to pay for damages, stripped of property, robbed, raped, arrested, harassed by mobs, and warned to leave Missouri by spring of 1839 ("History Far West").

Exodus to Illinois

The Saints faced severe hardships during their departure. Many families lacked adequate food, clothing, or shelter, enduring freezing temperatures and snow (Hartley). Most of the Latter-day Saints fled across the Mississippi River to Illinois (see fig.6), where compassionate residents of Quincy, appalled by Missouri's actions, offered them food, lodging, and employment opportunities ("Nauvoo, Illinois").

Figure 6. Depiction of Mormons crossing the Mississippi River to Illinois during winter by Carl Christian Anton Christensen, circa 1878.