Polygamy

The Mormon Church did not publicly acknowledge the practice of polygamy until 29 August 1852, when Orson Pratt, under the direction of Brigham Young, delivered a speech defending it as a fundamental church doctrine (Embry).

Initially, their isolation in Utah allowed the Mormons to practice polygamy openly and without interference ("Mormon Polygamy"). This would soon end, however, when James Buchanan, the last president before the Civil War, faced intense pressure from the newly-formed Republican Party. In the 1856 election, the Republican platform targeted the so-called "twin relics of barbarism"—slavery and polygamy. Slavery was not only legal at the time but also vital to the economy of 15 states. On the other hand, polygamy, primarily practiced by the Mormon Church in the far-off Utah Territory, was a much more manageable and politically convenient issue to address (“Utah War”).

Gubernatorial Replacement

Following his inauguration, President James Buchanan quickly sought to replace Governor Brigham Young with a non-Mormon governor, ultimately appointing Indian agent Alfred Cumming. Concerns about the Mormons’ theocratic structure threatening federal authority combined with reports from disaffected federal officials, including claims of burned judicial records and interference with U.S. mail, convinced Buchanan that the Utah Territory was in open rebellion (Fleek).

Rising Tensions

President Buchanan dispatched a military expedition, later known as the "Utah Expedition," to assert federal control. Commanded by General William Harney, the force consisted of roughly 2,500 troops, including infantry, cavalry, and artillery units. In response, Brigham Young mobilized the Nauvoo Legion. Though poorly equipped and inexperienced, the Legion used guerrilla warfare, much like they had in the Battle of Nauvoo, and scorched earth tactics like burning supply wagons and scattering livestock, to slow down the advancing army. The Saints also stockpiled resources and evacuated settlements to prepare for a potential siege. To prevent its use by federal troops, Mormon forces burned Fort Bridger and other strategic locations. The U.S. Army was forced to endure a harsh winter at makeshift quarters near the fort's ruins, suffering logistical challenges and supply shortages (Fleek; Poll).

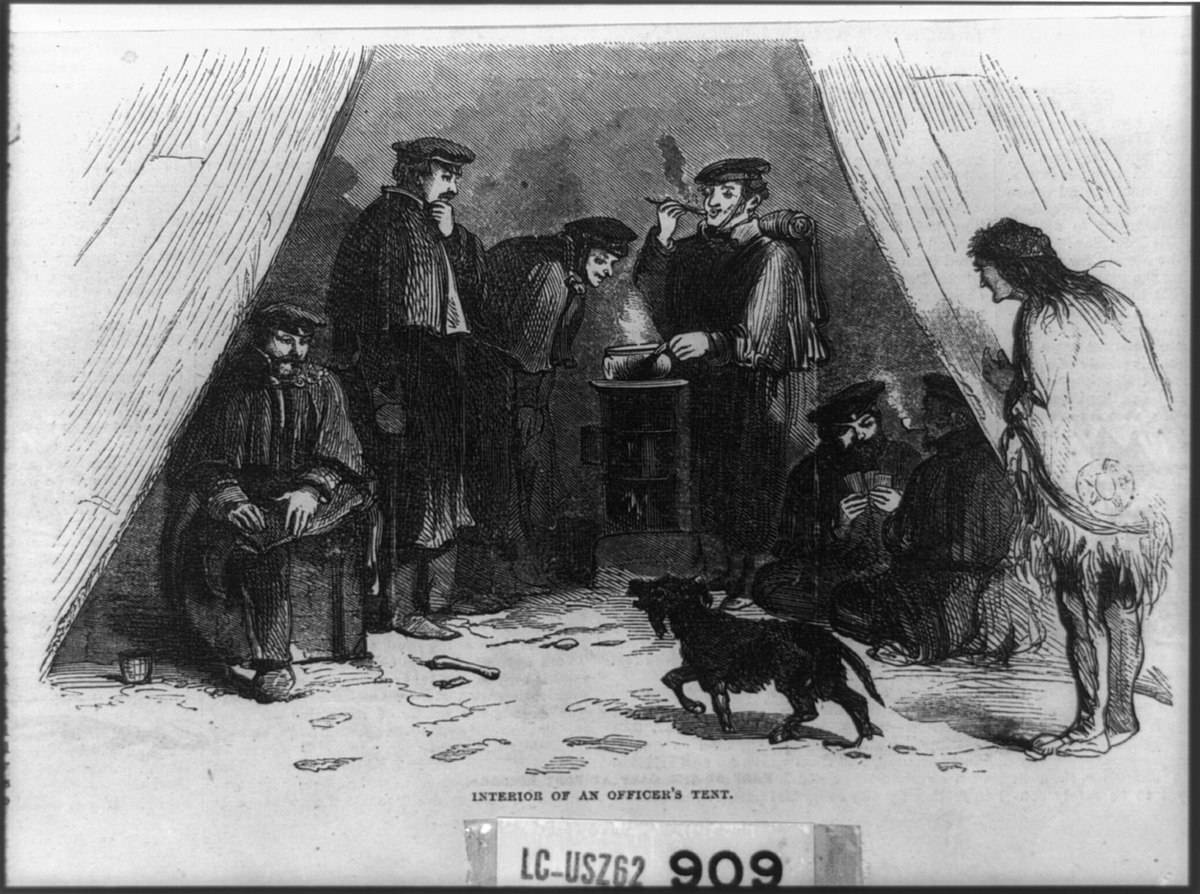

Figure 11. American officers during the Utah War, Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Mountain Meadows Massacre

On September 11, 1857, the Baker-Fancher party, predominantly emigrants from Arkansas traveling to California, were attacked by members of the Mormon militia, including Paiute Indians and members of the Nauvoo legion. After four days of siege, the Baker-Fancher party surrendered. The party was led out to the desert plain near Mountain Meadows, a popular water stop along the Old Spanish Trail. There, the militia members and Native Americans slaughtered the defenseless party, approximately 120 people in total, sparing only seventeen young children aged six and under (Reeves; “Mountain Meadows Massacre”).

Conclusion and Aftermath

The Utah War ended without large-scale bloodshed, largely due to the efforts of Thomas Kane, a non-Mormon ally of the LDS Church, who mediated between federal authorities and Church leaders. Governor Alfred Cumming replaced Brigham Young, entering Salt Lake City peacefully under assurances of Mormon cooperation. President Buchanan issued a general pardon to the Saints for acts of rebellion, seeking to de-escalate tensions. The U.S. Army also established Camp Floyd near Utah Lake to exert more federal control over local affairs. The war’s aftermath brought significant changes to Utah. The influx of soldiers and civilians disrupted the Saints’ isolation, bringing increased commerce, new businesses, and moral challenges such as alcohol consumption (Fleek).

Utah Statehood

During this time, tensions were still high between the federal government and Mormons, particularly over the practice of plural marriage. In 1882, Congress passed the Edmunds Act, which outlawed cohabitation and imposed fines and prison sentences for men living with more than one wife. This was followed by the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, which went even further by targeting the Church itself. This legislation dissolved the Church as a corporation and confiscated all property exceeding $50,000. In response, Mormons would evade federal antipolygamy laws by hiding, using aliases, or relocating to remote areas, often living in secrecy for years. Many faced arrest, fines, and imprisonment, while families endured economic hardships, separations, and fear of legal consequences. By the late 1880s, federal pressure was increasing significantly, forcing most of the church’s leaders to either go into hiding or risk imprisonment. In May 1890, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Edmunds-Tucker Act, allowing the confiscation of church property to continue. To prevent further loss of church temples and ordinances, President Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto after a revelation warned him of the dire consequences of continuing polygamy. He officially declared the end of the Church's practice of plural marriage on September 25, 1890, urging members to comply with federal laws. Furthermore, the Church began excommunicating members who persisted in practicing polygamy (Peterson).

Finally, with the renunciation of polygamy, the objections towards Utah’s statehood began to cease, and in 1896, Utah was admitted to the Union as the 45th state (Peterson).